Understanding How Plants Respond to Touch

Plants may not have nerves or muscles, but they are far from passive. In fact, they can sense and respond to physical contact in surprisingly complex ways.

One of the most fascinating of these responses is known as thigmomorphogenesis (pronounced: THIG-moh-mor-foh-JEN-uh-sis)— a process by which plants alter their growth in response to mechanical stimuli such as touch, wind, or vibration.

What Does “Thigmomorphogenesis” Mean?

The word comes from Greek roots: thigma (touch), morphe (form), and genesis (origin or creation). Together, they describe a change in form that originates from touch.

Thigmomorphogenesis is a well-documented biological phenomenon in which plants physically change their shape or growth habits when exposed to repeated mechanical stimulation. This might include regular brushing by animals, the pressure of wind, falling rain, or even human touch.

How Do Plants Detect Touch?

While plants don’t have a nervous system, they can sense touch through specialized structures like mechanosensitive ion channels found in their cell membranes. These channels detect pressure or deformation and open in response, allowing calcium ions and other signaling molecules to enter the cell. It’s like a gate swinging open in response to touch—once it moves, messages rush in to tell the plant how to adjust.

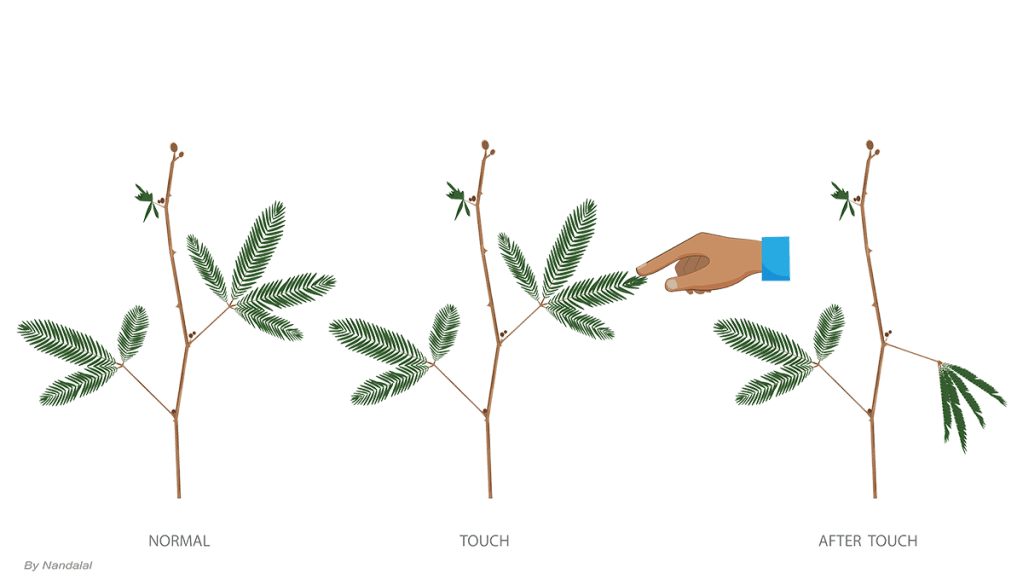

One dramatic example of this sensing in action is Mimosa pudica, a plant known for quickly folding its leaves when touched. This movement is called seismonasty and relies on rapid changes in turgor pressure rather than growth. While thigmomorphogenesis is much slower and subtler by comparison, both responses start with the same basic trigger: mechanical stimulation detected by these sensitive ion channels.

Fig .1 – Mimosa pudica folds its leaves in response to touch—a quick reaction called seismonasty.

After the initial signal, a cascade of biochemical responses leads to changes in gene expression. In this context, that means the plant temporarily adjusts how certain genes are activated, which in turn influences how it grows or develops. These changes happen within the plant’s lifetime and don’t affect its offspring—though in many cases, you might only notice the results through careful observation or measurement over time.

Among the genes involved are TCH genes (short for “touch” genes), which were first identified in studies of Arabidopsis thaliana (a small flowering plant commonly used as a model in plant biology). These genes activate rapidly after mechanical stimulation and are thought to regulate changes in growth patterns and hormone production.

Plant hormones such as ethylene, jasmonic acid, and abscisic acid also play a role in modulating the effects of mechanical stress, further influencing how a plant adapts to repeated touch.

Observable Effects of Thigmomorphogenesis

The most common result of thigmomorphogenesis is a sturdier, more compact growth habit:

- Shorter internodes (the spaces between leaves or branches)

- Thicker stems or trunks

- Delayed flowering (think of it as plant Pilates—stronger stems first, flowers later)

- Increased resistance to lodging (falling over)

These adaptations help plants better withstand environmental stressors such as strong winds, heavy rain—or even an over-eager dog tail.

Key Research and Findings

Thigmomorphogenesis has been studied for decades. The term was introduced by plant physiologist M.J. Jaffe in the 1970s, who explored how mechanical disturbances like wind or brushing could alter plant growth. His early experiments involved brushing bean plants and measuring differences in height and stem thickness compared to undisturbed controls.

More recent studies have continued to explore this phenomenon:

- Chehab et al. (2009) investigated how repeated mechanical stimulation affected gene expression and hormone activity in Arabidopsis. Their work confirmed that touch could significantly change plant development.

- Basu and Haswell (2017) reviewed the role of mechanosensitive ion channels in plant cells and discussed how plants convert mechanical signals into biochemical responses.

- A 2020 review published in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change explored how trees and other large plants respond to mechanical cues over long periods, with implications for forestry and climate adaptation.

Why It Matters

Understanding thigmomorphogenesis has practical applications in agriculture and horticulture. Growers sometimes use fans, brushing techniques, or gentle mechanical stress—like a low-key training session—to encourage sturdier seedlings that are better suited for transplanting or harsh outdoor conditions.

In larger-scale settings, this knowledge can help in breeding or managing crops that are less likely to bend or break due to wind and weather—particularly important in storm-prone or high-yield agricultural zones.

What about your houseplants?

Could touching or brushing your plants help them grow stronger? According to research—yes! Repeated, gentle contact can encourage sturdier, more compact growth in many plant species.

Want to see for yourself? Try a simple experiment:

Grow two similar plants side by side. Gently brush or tap one of them once or twice a day, and leave the other untouched. Measure their height, leaf spacing, and stem thickness over time—and take photos along the way.

You might be surprised by the difference!

Let us know what you discover by tagging us on social or sharing in the comments.

Kayla, Founder, Third Orbit Flora

Photo Credit: Banner – Adobe Stock Image by Kayla, Founder.; Fig. 1 By Nandalal Adobe Stock

Further Reading and Resources

- Chehab, E.W., Eich, E., & Braam, J. (2009). Thigmomorphogenesis: a complex plant response to mechano-stimulation. Journal of Experimental Botany, 60(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ern315

- Basu, D., & Haswell, E. S. (2017). Plant mechanosensitive ion channels: An ocean of possibilities. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 40, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2017.07.002

- Wikipedia: Thigmomorphogenesis

- Telewski, F. W. (2021). Mechanosensing and plant growth regulators elicited during the thigmomorphogenetic response. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 3, Article 574096. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/forests-and-global-change/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2020.574096/full

Leave a comment